We are absolutley delighted to announce that photographer Aaron Yeandle has joined the MAP6 collective!. Below is a brief interview where he discuses his photograhic practice, his influences and his latest projects.

Can you share with us your journey in photography – from your early inspirations and education to your current practice?

I first started photography when I studied an evening City and Guilds course. From that moment I wanted and needed to be a photographer. The following year, I left my full-time employment and began my journey into the world of photography. In this early stage of education my first inspirations were Richard Billingham, Martin Parr, Paul Reas, Nick Waplington and Rineke Dijkstra. These photographers revealed to me how the everyday world around us is so fascinating and how our society can be documented through photography. I was hooked on learning and began a BA (Hons) in photography. Throughout this period my work developed, and I became interested in other aspects of art and photography. In my second year I transferred to a BA in fine art. This was a period where I really learnt how to contextualise projects and ideas. Deep down, however, I wanted a photography degree rather than a fine art degree, and transferred back to photography for my final year.

During this time I was inspired by paintings, painters and different art movements such as the Romanticism, Realism and the New American colour movement. These influences helped to open my mind, understand lighting, and discern how photography plays an important part in sociology, politics, anthropology and history. Soon after, I began an MA in fine art where I learned how to write about my practice, and the different possibilities of exhibiting work such as installations and displaying and mounting artwork to suit the environment. I also lectured at the local college and university and spent another year studying for a PGCE, which allowed me to lecture in further and higher education. For the next few years I spent my time travelling, and ended up working as the senior technician in photography and media at a university.

With my practice I have become interested in how realism, romanticism and the imagination can be juxtaposed to create a narrative which tells a compelling visual story. For the past few years I have been exhibiting and working on numerous projects focusing on the unseen world of Guernsey’s communities, delving into social and historical aspects of the island. I have exhibited nationally and internationally, and my work has been seen in several international photographic festivals. I have also completed a number of international artist-in-residencies. Alongside my practice I provide educational workshops and present talks on my work.

What motivates and drives your photographic practice?

When I first discovered photography I had a deep need to somehow express myself creatively. Photography gave me something tangible to hold onto and provided me with some kind of inner peace. There is so much to capture, so many fascinating people and places to meet and photograph, and this is what drives and motivates me through my practice. Photography somehow allows me to put the world in order, which makes me feel calm amidst the chaos. It also allows me to provide a historical and social view of the world for the future.

Tell us a little about your major project Voice-Vouaïe and your recent exhibition in Guernsey.

For the last three years I have been working on a large-scale social and historical project on the island of Guernsey. The title of the project is Voice-Vouaïe. The aim of the project is to bring awareness and create a visual and audio archival record of Guernésiais, an ancient language of Guernsey with a long and distinctive history which derived from the Normans. Today, the number of original native speakers in Guernsey is in fast decline, and it is estimated that in 2021 there are possibly fewer than 150 fluent speakers, mainly aged over 80. In World War 2, Guernsey was occupied by the Germans for five years. Most of the children on Guernsey were evacuated to England, which is one of the main reasons why the language began to die out. The majority of people who took part in this historical project were not evacuated in WW2, and spent their childhood under the Nazi occupation. I felt the need to capture this critical and changing situation as an important part of Guernsey’s social heritage and for the future legacy of the Island. I feel that in documenting this social issue for the international community I have captured a part of social history, which can be so fleeting.

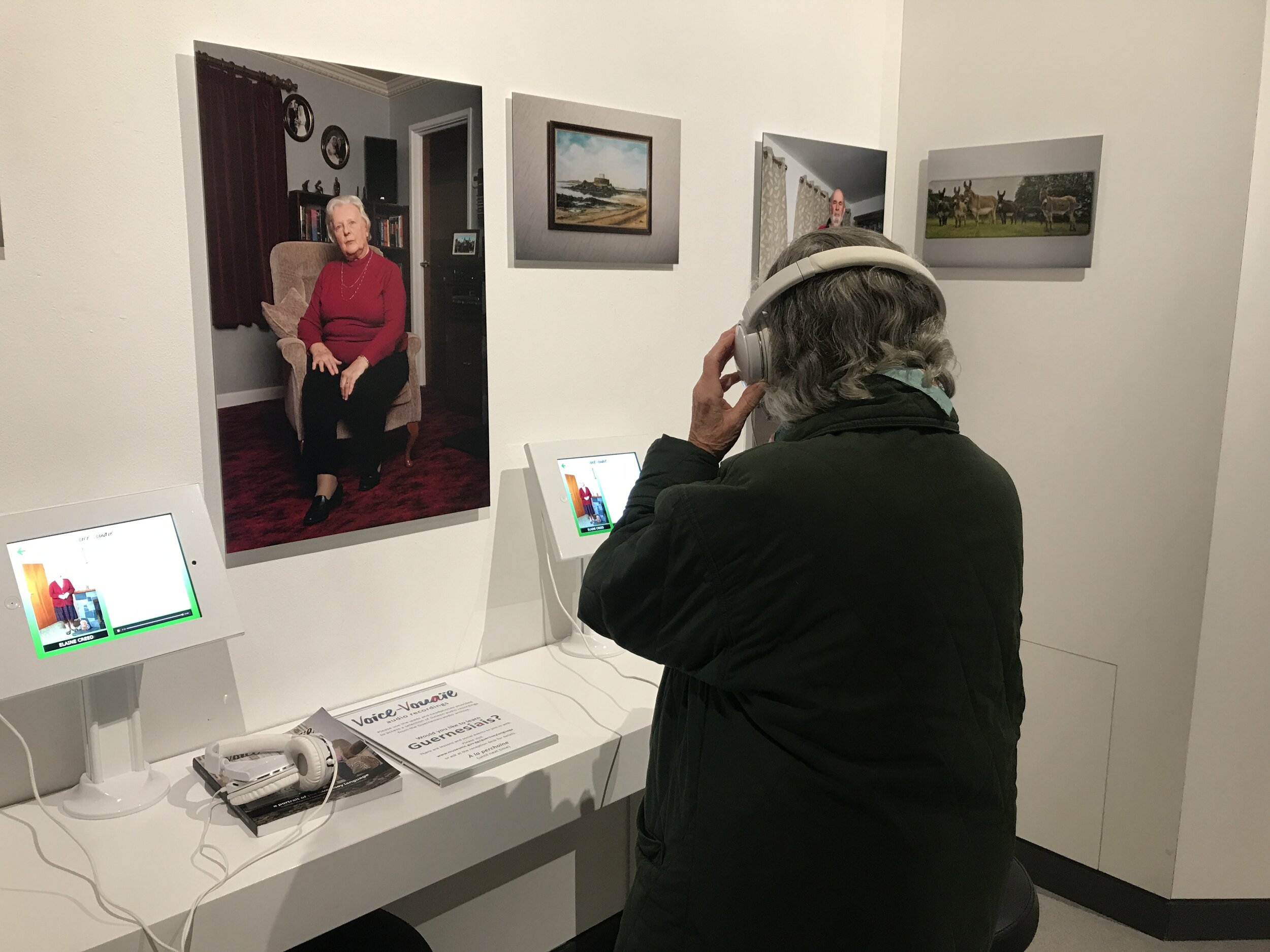

At the end of 2020 I showed Voice-Vouaïe in the Guernsey museum, with almost 200 images in this large-scale exhibition. To complement the photographs there was an opportunity to interact and listen to sound recordings of every person who took part in this historical project. In the gallery there was also a short film which featured the key people who made the project possible. There was also a complementary book published to go alongside the exhibition, which also acted as a guide and a gift for family members. We ran visits for different private and public organisations, as well as educational tours to primary, secondary and sixth form schools and educational talks at various events. Internationally the exhibition has created interest in Guernsey and the plight of the Guernésiais language. The next phase of the Voice-Vouaïe exhibition is now to take it on tour, to other countries that have their own endangered languages.

If you could work collaboratively with one photographer – living or dead – who would it be and why?

This is a hard question, but in the end I choose August Sander, who was a German photographer. He lived in a remarkable social and political time, where from the 1920s onwards Germany went through a great upheaval, changing from being a free and forward-thinking society to the radical constrictions of the mid-1930s. I feel that Sander was one of the first photographers who created what we now know as the ‘artist project’. He was also part of a collective called the Cologne progressives. Sander had a clear idea that he wanted to create a visual diary of everyday people and place. He would go outside the studio and take people to their everyday places or photograph them in their homes and in their own private surroundings. At this time this was unusual, as most portraits would’ve been taken in the studio. He was able to capture his subjects in an objective and non-judgmental way, and record time for the future of social history. Sanders’ work helped to confirm photography as a true art medium, and in some ways he was the first contemporary photographer of the 20th century.

What do you anticipate as being the advantages of working as part of a photography collective?

There are so many benefits of working in a collective. There is an opportunity to share experiences, knowledge, expertise and learn new skills from one other. There are also significant advantages working on a collaborative project, such as exhibiting together, providing and receiving feedback from peers, and facilitating each other’s growth as photographers. Furthermore, one of the great advantages is creating new contacts, which can develop into a community of artists and friends who are all striving for an outstanding photographic result.

What excites you about the future of photography?

Photography has been used for so many different reasons and has gone through many changes, compared with other art mediums. In recent years I have found that there seems to be a kind of renaissance back to analogue photography by the younger generation. Recently, I gave a two-day workshop on pinhole photography where the students were mainly young teenagers. We made cameras out of shoeboxes and made paper negatives, before developing the negs into positives using traditional darkroom chemicals. The younger students were fascinated with this process, and at the end of the course they went away with pinhole prints and were talking about how they would love to have their own darkroom. I find this exciting for the future of photography, even though my own practice has moved on from film. I can see there is a thirst by the younger generation to move away from digital photography and experiment. This may not be the future of photography; however, as long as there are photographic courses in schools, there will be a strong future for all types of photography.